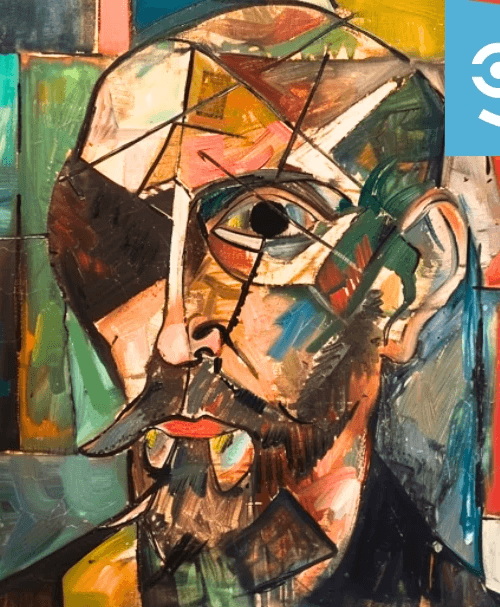

Painting with a lazy eye

The painter Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669) had a lazy eye and probably had trouble perceiving depth because of it. This is the conclusion reached by the American neurobiologists Margaret S. Livingstone and Bevil R. Conway of Harvard Medical in Boston after studying a large number of self-portraits of the Dutch painter.

The American researchers arrived at this conclusion after studying 36 self-portraits in which his eyes are clearly visible. In 24 of the 25 oil portraits, it is visible that the painter depicts his left eye slightly asymmetrically. And in all 12 etchings examined, it was Rembrandt's right eye that showed a deviation. Livingstone and Conway believe that the deviations indicate stereopsis, the scientific term for a lazy eye. They published this in the England Journal of Medicine.

Livingstone believes that it was not the painter's left eye but his right eye that was lazy, because he painted his own reflection. In the etchings he made, it was his right eye that showed a deviation, which can be explained by the fact that left and right are reversed during the printing process when etching. According to the two Harvard researchers, other famous painters, such as Pablo Picasso and Leonardo Da Vinci, also had eye deviations that did not lead to a negative influence on their artistic achievements. (...) According to Margaret Livingstone, they would have had the advantage of the lazy eye when transferring three-dimensional images into two-dimensional paintings or drawings. When teaching drawing or painting (even today) it is often asked to close one eye in order to see the image better and to be able to represent it on a plane. (...)

Stereoblindness could help any artist a little in depicting the world on a flat, blank sheet of paper, said Dr. Conway, who is also an artist. “Where do you start?” he said. “The real world is so rich in three-dimensionality, it’s hard to convey that richness of depth on paper.”

Artists use many tricks to create the illusion of depth, he noted. Things with higher contrast or higher resolution appear closer. Fuzziness and blueness push things into the distance. Such features are much clearer to the artist when stereoscopic cues are removed.

Finally, artists who are stereoblind have a natural ability to focus on the shapes of objects and the space around an object, often called negative space, Dr. Conway says. This gives them a natural advantage in developing “flat” images.

The condition Livingstone and Conway diagnosed, divergent strabismus, usually begins in early childhood when the muscles that align the two eyes don’t develop properly. Soon, one eye is focusing on what’s in front of it while the other eye drifts to one side. To prevent double vision, the brain learns to suppress the images from the wandering eye. People with the condition may have strabismus and/or lazy eye, Dr. Livingstone says. In either case, they are stereoblind, meaning their brains can’t combine the independent images from each eye to create depth perception.

Sources: livingstone.hms.harvard.edu, The New York Times, The New England Journal of Medicine, Trouw Arts Editorial